‘Over Tourism’ everyone clamours. Like it is something of the tourists own making. But what they should really be shouting is ‘Under Management’. Though admittedly it doesn’t make such a great soundbite.

The truth is most visitors don’t set out to cause the issues represented by over tourism. They might be quite lazy and just follow the crowd. But what are destinations doing to overcome that?

Last year in Australia I visited Uluru in the Northern Territory. About 300,000 people do so every year. I knew before arriving that the local Anangu people frown on the idea that you can climb Uluru. The Cultural Centre, tourist information, guides and signs all point out why this is.

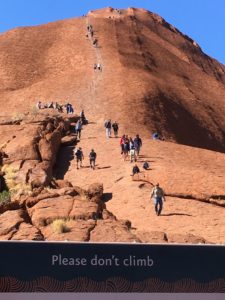

So I was surprised as I approached the rock to see a long line of bodies streaming up and down the side like a swarm of ants. It is estimated that about 1/6 of visitors to the park still climb up the rock, and while this is admittedly down from about 1/3 less than a decade ago it still accounts for about 50,000 people choosing to ignore the wishes of the custodians of Uluru.

It made me a bit sad and angry. Why would so many people ignore what was a very polite and well considered request not to climb. Well it definitely wasn’t because of a lack of signs including a big one at the bottom of the ascent. The psychology of the crowd in this instance may have had something to do with it. ‘If others are doing it then why can’t I?’ Or the visual prompts may have caused some confusion. ‘I can see the signs but they have put a guide rail and ropes there, so it must be okay’.

And this problem exists everywhere that tourists go. I’ve been to Venice. The waterfront by St Marks Square and the square itself were packed. But there was mile upon mile of narrow and off-the beaten alleyways with hardly a visitor in sight. A short hop on a boat across to the Venice Lido offered an altogether different experience which was calm and peaceful.

In Brighton, the majority of visitors exit the railway station and with the sea in sight, head straight down West Street along an approach that lacks any quality whatsoever. Yet 100 metres to the left are the North Laine and Lanes a quirky and eccentric offering of independent shops and cafes, cultural experiences and narrow streets that you won’t find anywhere else and which offer a much more interesting route to the seashore.

At the Grand Canyon, the crowds gather around the main visitor centre and the trails that start there. But go a few miles to the East to Shoshone Point and you could follow trails and spend the day watching the sun rise or set and not see another soul.

The list of places that are supposedly ‘over crowded’ but which actually have plenty of capacity goes on and on.

Maybe visitors don’t know about these other options. Maybe they see the crowd and think ‘they look like they know what they are doing, I’ll just follow them’. Maybe they are lazy and ill-informed. Who knows? The answer is probably a mix of all of these things.

The problem isn’t one of too many tourists. It is one of how they are managed. And there are good examples of the way in which places are trying to deal with the problems.

Many proposed solutions have centred around additional fees, taxes and charges to help restrict numbers or tighter access controls. But there are lots of other imaginative ways to help manage and disperse visitors to areas where their spending could have a more positive impact.

Improved design of public realm to support wayfinding, improved directional signage, creating identifiable quarters, use of lighting, street art, landscaping and volunteers to help change the behaviours which lead to overtourism. Use of digital tools, guides and trails can all help direct visitors to less explored corners of popular destinations.

At Uluru national park, the authority has created a single space of about 1km in length where everyone wanting to see the rock and its changing colours at sunset or sunrise can go. Of course hardly anyone thinks putting more tarmac down in the national park is a great idea. But concentrating this activity in one area where it can be managed is preferable to having vehicles spread throughout the park and damaging wildlife and the environment over a wider area.

Visitors are open to influence by those managing a destination. Especially if you can come up with a creative alternative. So rather than being 1 in 50,000 people climbing Uluru this year, why not be one of only a handful that walk around the base. You’ll see more, experience more and have a better boastable experience. And if that doesn’t work you can always take the rope away.